|

review

web |

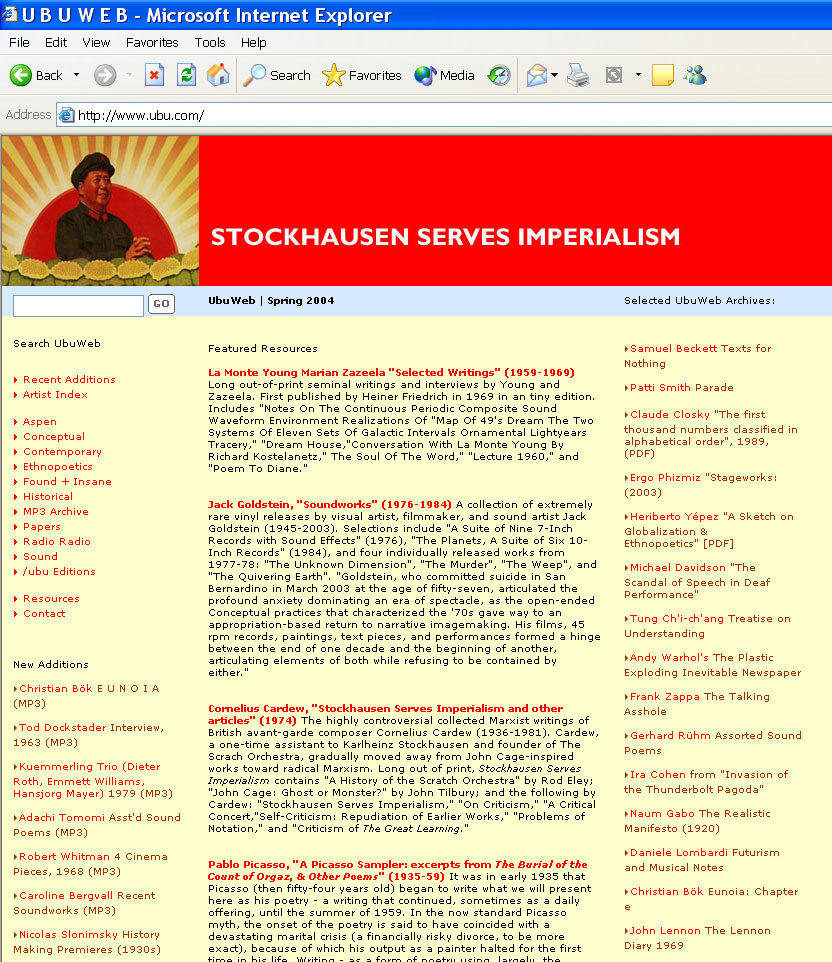

UbuWeb

by Donato Mancini |

The name of this site refers to the works of writer and 'pataphysician Alfred Jarry (1873 -1907) -- specifically, Jarry's dramatic cycle featuring his mytho-Dada character, the "blundering and monstrous" Ubu. As perhaps the most important precursor to Dada, Jarry's writing helped unleash a range of destructive, sub-terranian forces within literature. As André Breton wrote: "…literature, from Jarry on, is dangerously booby trapped, like a mine field." What's represented on Ubuweb, then, are all the most explosive genres of poetic literature that got their jump-start with Jarry, achieved greater significance slightly later with Zurich Dada, then enjoyed a major international renaissance in the 1960s. While among the most important recent developments in the literary arts, these genres have also consistently been the most marginalized: concrete / visual poetry, sound poetry, and all kinds of flagrantly genre-defying conceptual textualities. Ubuweb represents them directly, by showcasing the work itself and featuring critical papers on the subject, critical notes, radio interviews with artists, and "Ubuweb Editions" -- PDF re-publications of significant recent books. Reading through some of the critical writings gathered in the "Ubuweb Papers" section, we find that a number of the editor-contributors believe that visual / concrete poetry as a genre has at least largely failed to make significant artistic advances since its last great moment in the 60s. It's speculated that this failure is due to print being exhausted as a medium for the genre. That is possible, but it seems a somewhat facile thing to say -- declaring things "dead" is a kind of snot-ball avant-garde maneuver. I think the more likely reason that the medium has failed to progress significantly is the poor distribution of the work. Except for a handful of anthologies, there hasn't been quite enough material available for building a collective sense of the distinct history and progression of the genre; something that is necessary to the artistic health of any medium. |

|

"Essentially

a gift economy, poetry is the perfect space to practice utopian politics.

Freed from profit-making constraints or cumbersome fabrication considerations,

information can literally 'be free': on UbuWeb, we give it away and have

been doing so since 1996." -- from the editors |

|

But with Ubuweb (and certain other resources), this lost Atlantis of dazzling textual improbabilities is at last becoming handily available. No longer will it be so sparsely scattered, or vaulted away in "Special Collections." Within a few days of reading, any young, middle-aged or old person with Internet access will be able to get a pretty good handle on what's been done. These new poets will then be able to set off on their own literary adventure possessing a fair map of the known world; their works will naturally engage the past rather than merely repeating it. And as Ubuweb continues to grow (as it has and surely will), it will only become ever more valuable in this respect. Ubuweb could in fact be just what poetry doctor ordered. In

bringing all this to us, Ubuweb encompasses many of the given compositional

possibilities, and conceptual paradigms of the web page. Ubuweb is

sometimes an archive, sometimes a library, sometimes an anthology,

sometimes an interactive multimedia application, sometimes a discussion

forum. From its development so far, we can imagine that most useful

aspects of web technology still left out will eventually be represented

-- even VR. Among the most significant (and web-specific) contributions

of Ubuweb -- specifically as an archive -- is its fantastic MP3 and

Real Media collection of sound poetry. If I'm not wrong, there has

never been as complete and accessible a resource of sound poetry.

Sound poetry is a fascinating genre because, despite having a history

that goes back to a trigger moment of Dada -- who hasn't seen the

pictures of Hugo Ball in his lobster suit reciting Karawane? -- it

has never been much acknowledged. For a specialized interest like

sound poetry, which has little monetary value attached to it, there

is no better place than the Web to house such a collection. There

is still a lot more material to gather, of course, but unlike an anthology

or even a library, there is practically no limit to how big Ubuweb

could become over the years. I don't doubt that a lot more poets will

become seriously interested in sound poetry thanks to Ubuweb.

|

"The

greatest cyberpoem would be an online application that provided you with a an interesting text and a robust interface with which to manipulate it. In other words, a word-processor." -- Roger Pellett |

As for other shapes of the future, the editors note: "Concrete poetry's historical move from the poetic line to the visual linguistic constellation predicted parallel moves in computing from command line interface to graphical user interfaces. With concrete poetry's implied dynamism and hyperspace, the concrete poets seemed to be begging for multimedia to enter into their practice. Since the technology was not yet available, they stuck with the page. With the advent of the web, we've seen the fulfillment of this tendency." Naturally, then, Ubuweb fulfills its mandate by offering a fascinating representative sample of this so-called 'cyberpoetry,' a truly 21st century genre still in its embryonic phase. A lot of the cyberpoems on Ubuweb are still online translations of old media. Brian Kim Stefans' beautiful dream life of letters, for example, is a cartoon starring letters and words (as are many of the other cyberpoems). Such works indeed fulfill the dreams of countless 60s concretists, but except for the expense and time involved, as well as important questions of distribution, they might as well have been hand-drawn. A number of other cyberpoems are basically flip-books of gifs, animated permutation poems, or are in substance little different from analog collages. Fine pieces, but we can legitimately ask, as Stefans does: where's the 'cyber'? Certain other poems on Ubuweb however do move into a genuinely 'cyber' space. One of the most significant formal possibilities that the Web offers for textual arts is that of broadly 'collaborative' modes of text-production. It is a post-modern commonplace that a reader is highly complicit in the creation of a text. Web technologies are making this important concept become literally true by allowing texts to be generated through the 're-writing' by every person who reads them. Poets like Alan Sondheim, Brian Lennon and Jim Andrews, Ted Warnell, Guerilla Poetry and Dan Farrell -- as you'll see on Ubuweb -- have begun to open this fruitful avenue. Working in this direction, cyberpoetry could indeed be the next significant blast in the chain set off by Jarry. It threatens the concept of authorship, copyright, and control in an even deeper way, I think, than an automated 'robo-poetry' (the other major anticipated mode of cyberpoetry) does / will, while also being something more than a fancy new brand of the aleatoric. Not that 'the author' is likely to die anytime soon (yes, novels are afoot) but we can see that the Web has already created profound changes in language, and consequently is changing literature -- in some cases quite beyond recognition. As Lucas Mulder points out, these possibilities of cyberpoetry are therefore not only meaningful as historical developments within the realm of poetry but also with regard to Internet art and interactivity (and I'll add, language) as a whole. |

|

| "I

don't believe that technology creates improvement, but rather that we need

to use the new technologies in order to preserve the rather limited cultural

spaces we have created through alternative, nonprofit literary presses and

magazines. This is a particularly important time for poetry on the net because

the formats and institutions we are now establishing can provide models

and precedents for small-scale, poetry intensive activities." -- Charles Bernstein, 1995 |

|

|

To continue on this speculative line, I also don't think that the best cyberpoetry will be one that attempts to be totally synaesthetic -- not a poetry 'feelies' with full-body cybersex suits, scent-o-matics and glib techno soundtracks. While crossing media in controlled ways is a proven strategy, the Wagnerian quest for a Gesamptkunstwerk has often enough proven wholly Quixotic, or the product of a gluttonous sensibility. More = better = Mega Poetry. One of the most infernal temptations of New Media is clearly towards such numbing overkill, and so we most appreciate the subtler 'cyberpoems' on Ubuweb, even when they are a little short on 'cyber.' Not the least of the problems that the idea of a cyberpoetry creates, is that of genre distinctions. Happily, where cyber 'text-art' ends and cyber 'poetry' begins is already very vague. As Brian Kim Stefans writes, "…the so-called cyberpoetry which is good is anything but 'cyber,' it can better be defended under some other label, like art." I must agree and add: I think the best cyberpoetry is (and will be) closest to the material cleverly organized on Ubuweb under the heading of "conceptual." And as the cyber aspect of the genre develops, we'll probably discover that the poetry aspect will turn out to be little more than a regional accent. Whatever happens, it'll be a good show -- the show of the century -- and one of the best places to watch it will be Ubuweb. |

"Where

previously electronic poetry focused on the paths a reading could take within a larger context, text linking to text linking to text, electronic poetry can now take things a step further and examine the process involved in making a poem, allowing the poem to be 'rewritten' and thus 'reread' by users, via simple inputs such as clicking or dragging the mouse." -- Lucas Mulder |