|

CG03: The Art of SIGGRAPH 2003 is an exhibition that embodies

the rich spirit of artistic truth and expression through digital

technologies. Although there are valid cautions concerning the

mix of art and the technological ethos, CG03 is evidence that

artists can balance technology with meaning without having technology

dominate them or their ideas. Jeanne Randolph coined

the term technological ethos [Randolph 91], or an ideology that

includes a worldview that is productive and meaningful for many

instances, especially industry and science. In a recent presentation

at the Banff New Media Institute [Randolph03], Randolph

explained that the technological ethos includes an ethic of "getting

the job done," which, as she pointed out, is appropriate

for non-cultural work. It does not, however, include the same

ethics and meaning that artmaking embodies. In the context of

art and science collaborations, Randolph explained that those

working from the philosophical stance of the technological ethos

might not understand that shaping culture is not necessarily a

job; rather, it is about creating meaning. Art, which she includes

in cultural work, is inherently about meaning and ethics. She

claimed that when an artist enters into collaboration with those

who hold to the technological ethos, she puts meaning and ethics

into jeopardy. She further argued that technology can seduce an

artist, and in so doing, can inhibit creativity, ethics, and meaning

and contribute to exploitation.

I propose that those artists who use contemporary digital technology

are in a way collaborating with others who have created it

and are making a choice to do cultural work within the realm of

the technological ethos. I believe that, in a time characterized by

our society's obsession with technology, Randolph's concerns

about seduction and the loss of meaning in such collaborations

are compelling; however, they do not have to apply.

Instead, many artists who make works using digital technology

bend the medium so it works to serve the artistic ethics of truth,

meaning, and expressive ideas. The works in the SIGGRAPH

2003 art exhibition are lucid examples of how artists can balance,

if not overcome the technological ethos to create lush,

aesthetically pleasing, and meaningful works that explore

ideas such as the self, culture, politics, ethics, and the effect of

digital technology on art and society. According to the chair of

CG03 Michael Wright,

"...[the works represent] artists' ideas, thoughts, and truths,

reflecting the layered, non-linear, pluralistic nature of our

times..." [Wright03]. The exhibition contains an astonishing

189 works including sculpture, two-dimensional pieces, digital

video and animation, as well as six critical essays. After 30

years of SIGGRAPH annual conferences, the 2003 art gallery

returns to the roots of computer graphics with a focus on animation

and video, print, and sculpture, thus emphasizing artistic

expression that transcends the underlying technology.

The artists in the SIGGRAPH 2003 exhibition directly challenge

the technological ethos to address truth, aesthetics,

meaning, and ethics. Works by Quintin Gonzalez, Dorothy

Krause, Tina Bell Vance, Celeste Joy Greer (et al.), and Joon

Y. Lee, to name a few, twist and reconfigure technology in

ways that equalize any negative residue that a technically

obsessed culture might leave on expressive artworks.

Quintin Gonzalez's Ghost Of Time (Figure 1) is a narrative

series of images that show movement through the marking of

surface kinetics. His abstraction of the human form evokes

mysticism that builds a connection between the abstracted digital

representation of humans and the sacred. The blurred

faces appear ominous yet approachable and their implied

movements evoke the equally contradictory emotions of fear

and curiosity. The faces seem to flow from frame to frame,

creating a formal balance of color and design. The work

includes natural and digital samplings that the artist uses to

create a new meaning played out through the interaction

between the machine and the artist. According to Gonzalez,

"This new meaning of digital technology's function

is one where the machine serves an esoteric, spiritual,

and often an irrational purpose." Perhaps the

machine influenced the work, however, it is the

interplay between Gonzalez and the computer that

creates the artists' final imagery. He harnesses the

narrative language that technology is capable of

and presents it as a digital aesthetic.

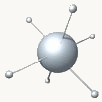

Dorothy Krause's sculptural works (Figure 2) also

play a part in defining a digital aesthetic, however,

hers is more directly part of the larger art continuum.

In the near future, as Ann Spalter [Spalter03]

predicts, digital arts will be embedded in much of

what we do artistically to the point of making it

almost invisible. Krause's work grows from the tradition

of her formal training as a painter and her

natural inclination towards collage. She uses simple

materials such as plaster, tar, wax, and pigment

along with contemporary technology to create

works that are timeless and evoke emotions such

as hope, fear, and immortality. Although not literal,

her work directs the viewer to look beyond the initial

impression for hidden truth. Vengeance Is Mine is

an accordion book that leads the viewer down a

narrative path of symbolism and meaning. Strapped

is a rich mixed media image that pictures two feminine

faces next to one another, thus setting up possibilities

for the viewer to contemplate the relationship

between two people or see them as sides to

a single self. In the end, her work evokes individual

responses that carry meaning void of technical

overindulgence.

Dorothy Krause's sculptural works (Figure 2) also

play a part in defining a digital aesthetic, however,

hers is more directly part of the larger art continuum.

In the near future, as Ann Spalter [Spalter03]

predicts, digital arts will be embedded in much of

what we do artistically to the point of making it

almost invisible. Krause's work grows from the tradition

of her formal training as a painter and her

natural inclination towards collage. She uses simple

materials such as plaster, tar, wax, and pigment

along with contemporary technology to create

works that are timeless and evoke emotions such

as hope, fear, and immortality. Although not literal,

her work directs the viewer to look beyond the initial

impression for hidden truth. Vengeance Is Mine is

an accordion book that leads the viewer down a

narrative path of symbolism and meaning. Strapped

is a rich mixed media image that pictures two feminine

faces next to one another, thus setting up possibilities

for the viewer to contemplate the relationship

between two people or see them as sides to

a single self. In the end, her work evokes individual

responses that carry meaning void of technical

overindulgence.

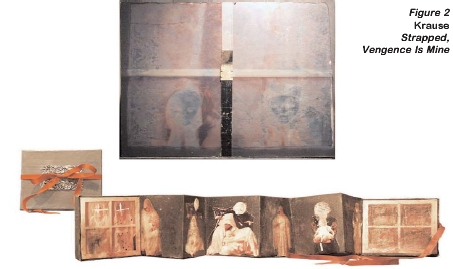

Like Krause, Tina Bell Vance makes works that visibly

extend established media into the digital realm.

Vance's work appears both painterly and photographic

at once and in effect, challenges traditional

forms. More importantly, she uses digital technology

to direct these new forms into meaningful work

that comments on personal and political issues.

With her works in CG03, Still Life With Hands, Still

Life With Foot, and Still Life With Torso (Figure 3),

Vance calls into question politics associated with

the body. For example, what are the implications of

body dismemberment? What could the erosion of a

body imply? Although decaying, these eroding

body parts are quite beautiful and, pictured next to

succulent fruits, posed in a way that references yet

redefines the traditional still life. Perhaps this is a

commentary about age or decay and the beauty in

the process. All these notions touch on issues as

complex as the role of the body in technology or as

simple as the beauty of decay. In showing work

that evokes such ideas, Vance addresses ethical

issues that are key to the artist's role in our society.

Although facilitated by technology, her work serves

and helps define and reflect our culture. At the

same time, it is the technology that feeds some of

the issues she raises, thus it acts as meaningful

capital in the flow of creative thought.

Like Krause, Tina Bell Vance makes works that visibly

extend established media into the digital realm.

Vance's work appears both painterly and photographic

at once and in effect, challenges traditional

forms. More importantly, she uses digital technology

to direct these new forms into meaningful work

that comments on personal and political issues.

With her works in CG03, Still Life With Hands, Still

Life With Foot, and Still Life With Torso (Figure 3),

Vance calls into question politics associated with

the body. For example, what are the implications of

body dismemberment? What could the erosion of a

body imply? Although decaying, these eroding

body parts are quite beautiful and, pictured next to

succulent fruits, posed in a way that references yet

redefines the traditional still life. Perhaps this is a

commentary about age or decay and the beauty in

the process. All these notions touch on issues as

complex as the role of the body in technology or as

simple as the beauty of decay. In showing work

that evokes such ideas, Vance addresses ethical

issues that are key to the artist's role in our society.

Although facilitated by technology, her work serves

and helps define and reflect our culture. At the

same time, it is the technology that feeds some of

the issues she raises, thus it acts as meaningful

capital in the flow of creative thought.

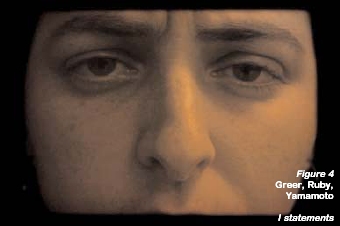

Just as digital technology has extended and fed

sculptural and image-based media, it has also

impacted time-based media. Although work based

in time goes back to the beginning of human artistic expression, digital

processes have added to this kind of art, thus broadening the possibilities in

media such as video, film, animation, and in interactivity. The apparent ease

of using such technology has seduced many people, but artists making

meaningful and aesthetically rich art have thankfully prevailed. One example

from the CG03 gallery is Celeste Joy Greer's, Nicole Ruby's, and Mark

Yamamoto's digital video I Statements (Figure 4), which is a piece about

pain and the cycles associated with it. The artists use the word 'I' to make the

viewer think about the individual pain of the speaker. The use of this kind of

micro-introspection invites the viewers to go into themselves to then emerge

with some kind of meaningful connection with the artist. The artists strive

to speak to each person and make a unique connection. The act of

connecting becomes universal in that no viewer emerges untouched. This

is part of the core of art, and computer graphics technology can enable it.

In making the video, there were moments that were too personal for the

artist to communicate in front of her collaborators. In their place, the camera

stood collecting the information, preparing it for digital manipulation that

would make the segment palatable. The digital processing enabled the

artists to work with raw emotion that they could manipulate and translate

into a form that others could enter. The work is a 30-minute "stream of consciousness"

expression of pain that was distilled down from hours of

footage and then stitched together to form

a poignant work about grief. Rather than

directing and overwhelming the work, digital

technology made possible the transformation

of raw emotion into a work of

art. The idea of processing emotion

through technology and ending with art

that embodies mediated emotive

intensity speaks to the current and

future possibilities of human co-existence

with technology and the balance that we

can enforce with the technological ethos.

In addition to processing already existing

forms of media, such as film and video,

computer graphics technology provides a

way for artists to make digital animations

that are wholly created within the space

of the computer, minus a few scanned

textures. When artists are not mimicking

film or other existing media, these animations

often create works that are unique

in look and offer a new sense of reality.

We have come to think of film as reality

yet it is in fact only one form of it.

Perhaps, as Lev Manovich suggests

[Manovich96], the different reality that the

digital medium yields is one that is overreal,

or hyper-real. Computer graphics

technology is now capable of giving us

more information than we can process,

certainly different from the reality that we

have come to know from traditional film

and photography. This intriguing transformation

can be technologically seductive

to the point of technical obesity, and there

are certainly plenty of Hollywood fiascos

that support this thesis. However, serious

artists are playing with this new form of

reality to create works that, as I have

shown with other digital works from the

SIGGRRAPH 03 exhibition, embrace the

values of art.

Just as digital technology has extended and fed

sculptural and image-based media, it has also

impacted time-based media. Although work based

in time goes back to the beginning of human artistic expression, digital

processes have added to this kind of art, thus broadening the possibilities in

media such as video, film, animation, and in interactivity. The apparent ease

of using such technology has seduced many people, but artists making

meaningful and aesthetically rich art have thankfully prevailed. One example

from the CG03 gallery is Celeste Joy Greer's, Nicole Ruby's, and Mark

Yamamoto's digital video I Statements (Figure 4), which is a piece about

pain and the cycles associated with it. The artists use the word 'I' to make the

viewer think about the individual pain of the speaker. The use of this kind of

micro-introspection invites the viewers to go into themselves to then emerge

with some kind of meaningful connection with the artist. The artists strive

to speak to each person and make a unique connection. The act of

connecting becomes universal in that no viewer emerges untouched. This

is part of the core of art, and computer graphics technology can enable it.

In making the video, there were moments that were too personal for the

artist to communicate in front of her collaborators. In their place, the camera

stood collecting the information, preparing it for digital manipulation that

would make the segment palatable. The digital processing enabled the

artists to work with raw emotion that they could manipulate and translate

into a form that others could enter. The work is a 30-minute "stream of consciousness"

expression of pain that was distilled down from hours of

footage and then stitched together to form

a poignant work about grief. Rather than

directing and overwhelming the work, digital

technology made possible the transformation

of raw emotion into a work of

art. The idea of processing emotion

through technology and ending with art

that embodies mediated emotive

intensity speaks to the current and

future possibilities of human co-existence

with technology and the balance that we

can enforce with the technological ethos.

In addition to processing already existing

forms of media, such as film and video,

computer graphics technology provides a

way for artists to make digital animations

that are wholly created within the space

of the computer, minus a few scanned

textures. When artists are not mimicking

film or other existing media, these animations

often create works that are unique

in look and offer a new sense of reality.

We have come to think of film as reality

yet it is in fact only one form of it.

Perhaps, as Lev Manovich suggests

[Manovich96], the different reality that the

digital medium yields is one that is overreal,

or hyper-real. Computer graphics

technology is now capable of giving us

more information than we can process,

certainly different from the reality that we

have come to know from traditional film

and photography. This intriguing transformation

can be technologically seductive

to the point of technical obesity, and there

are certainly plenty of Hollywood fiascos

that support this thesis. However, serious

artists are playing with this new form of

reality to create works that, as I have

shown with other digital works from the

SIGGRRAPH 03 exhibition, embrace the

values of art.

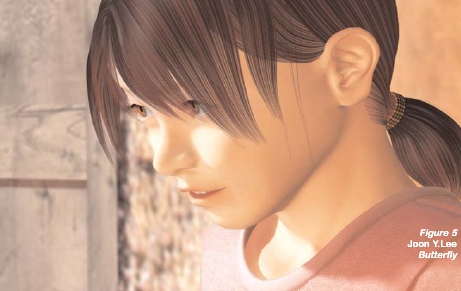

Joon Y. Lee employs the hyper-real quality

of computer graphics technology to

shock the audience in his digital animation

Butterfly (Figure 5). The piece starts

off innocently, if not cliché, with a solemn

girl who is cheered by a passing butterfly.

As the insect interacts

with her she is

pulled into its beauty

and learns to trust

and follow it.

Intentionally or not,

the butterfly leads

the girl to a landmine

where she meets her

death. The work is

oozing with political

irony and implications.

Some questions

include, "What

political body could

the butterfly represent?,"

"Where is

this taking place?," "Who planted the

landmine and why?," to name a few. The

artist uses the hyper-real nature of digital

animation to bring the audience into a

pleasing and overly sappy world only to

shock them into political reality.

The altered reality of the digital medium is

an optimal way for artists to suggest a

new way of seeing things, thus taking a

part in defining our culture. As such, the

works in CG03: The Art of SIGGRAPH

2003 play a part in characterizing the digital

aesthetic, one that brings along with it

the traditional art values of ethics and

meaning. After all, art includes a role in

defining culture, one that is inherent to

art regardless of the medium.

In The Language of New Media,

Manovich [Manovich01] challenges us to

help fully define the expressive possibilities

and attributes of digital and new technologies.

This will force artists to probe

technology and in some ways make commentary

about it, which should not to be

confused with the technological ethos. It

is good to be cautious and to heed the

temptation to let the obsession with technology

take over the 'truth' in art, or defining

culture. As evidenced by the work in

the SIGGRAPH 03 art exhibition, there

are many artists who have managed to

work the technology in their favor and

who have kept overindulgence in it at bay

to create rich and meaningful works of

art.

Joon Y. Lee employs the hyper-real quality

of computer graphics technology to

shock the audience in his digital animation

Butterfly (Figure 5). The piece starts

off innocently, if not cliché, with a solemn

girl who is cheered by a passing butterfly.

As the insect interacts

with her she is

pulled into its beauty

and learns to trust

and follow it.

Intentionally or not,

the butterfly leads

the girl to a landmine

where she meets her

death. The work is

oozing with political

irony and implications.

Some questions

include, "What

political body could

the butterfly represent?,"

"Where is

this taking place?," "Who planted the

landmine and why?," to name a few. The

artist uses the hyper-real nature of digital

animation to bring the audience into a

pleasing and overly sappy world only to

shock them into political reality.

The altered reality of the digital medium is

an optimal way for artists to suggest a

new way of seeing things, thus taking a

part in defining our culture. As such, the

works in CG03: The Art of SIGGRAPH

2003 play a part in characterizing the digital

aesthetic, one that brings along with it

the traditional art values of ethics and

meaning. After all, art includes a role in

defining culture, one that is inherent to

art regardless of the medium.

In The Language of New Media,

Manovich [Manovich01] challenges us to

help fully define the expressive possibilities

and attributes of digital and new technologies.

This will force artists to probe

technology and in some ways make commentary

about it, which should not to be

confused with the technological ethos. It

is good to be cautious and to heed the

temptation to let the obsession with technology

take over the 'truth' in art, or defining

culture. As evidenced by the work in

the SIGGRAPH 03 art exhibition, there

are many artists who have managed to

work the technology in their favor and

who have kept overindulgence in it at bay

to create rich and meaningful works of

art.

References:

[Manovich96] L. Manovich. "The

Paradoxes of Digital Photography" in

Photography After Photography : Memory

and Representation in the Digital Age.

Hubertus v. Amelunxen, Stefan Iglhaut,

Florian Rötzer (eds.) Amsterdam: G+B

Arts, 1996.

[Manovich01] L. Manovich. The

Language of New Media. Cambridge,

Mass: MIT Press., 2001.

[Randolph 91] J. Randolph.

"Technology as Metaphor" in

Psychoanalysis & Synchronized

Swimming and other writings on art.

Toronto: YYZ Books, 1991.

[Randolph 03] J. Randolph. 'Creative

Tensions and Identities' during "The

Beauty of Collaboration: Manners,

Methods, and Aesthetics" at the Banff

New Media Institute (BNMI), May 22-25,

2003.

[Spalter03] A. Morgan Spalter. "Will There

Be 'Computer Art' in the Year 2020?" in

SIGGRAPH 2003 Electronic Art and

Animation Catalog. New York, New York:

The Association for Computing

Machinery, Inc., 2003.

[Wright03] M. Wright. Exhibition

Introduction, in SIGGRAPH 2003

Electronic Art and Animation Catalog.

New York, New York: The Association for

Computing

Machinery, Inc., 2003.

|