review exhibition

documenta11_platform5 -- exhibition as research: hope childers / susan ryan

download pdf

|

intelligent agent vol. 3 no. 1

review exhibition documenta11_platform5 -- exhibition as research: hope childers / susan ryan download pdf |

Documenta11_Platform5: Exhibition as Research

|

exhibition |

|

In 1955, painter Arnold Bode, with help from art historian Werner Haftmann, organized an international art exposition, called "Documenta," that would serve to reinstate modern art in an isolated, post-war Germany. Every four or five years since then, the small city of Kassel (home of the Brothers Grimm of fairy tale fame) has hosted the event which, this summer, has drawn more than a million visitors. This year's Documenta, the eleventh, extends from the traditional site, the Fridericianum and nearby Documenta Halle, to newly acquired spaces including the Binding Brauerei, an old converted brewery across town accessible by shuttle bus, and also a somewhat hidden additional venue near the platforms of the train station. Much discussion has been generated by the exhibition, most of which has focused on the show's huge size and its degree of "internationalism." Few, however, have questioned the larger impact of Documenta's curatorial and presentational agendas. There are two historical generalizations that can be made about Documenta, which supply a conceptual backdrop for its mountainous offerings this past summer: (1) Because they are more thematic than other international exhibitions like the Venice Biennial, Documentas customarily articulate, in a curatorial manner, major concerns and debates concerning art at the historical moment of each Documenta's presentation (recall the return of monumental painting -- especially German monumental painting-- not to mention Joseph Beuys's historic "7000 Oaks" at Documenta VII). (2) Documentas since the 1960s have been concerned with art's role in society, something that is rarely a focus of museum blockbusters in America, Britain, Italy, or France. The Documentas, rightly so, have been a source of national pride in Germany, and all of them, including D11 (to use the the common abbreviation), are significantly contextualized within the history of Documentas, as D11's website and numerous pamphlets and publications related to this year's event make clear. And, as with all long-standing art institutions, Documenta's sense of self-importance permeates its environments, particularly noticeable this year in the regimented patrol of young blue-vested "guides" who zealously enforced Documenta's rules and regulated the number and behavior of viewers in exhibition rooms. The self-referential character of Documenta has attracted criticism from the event's detractors, who, in the past, have indicted the exhibition for favoring the privileged and elitist sectors of the art world. This year's Documenta has deflected such accusations by having the first-ever non-European Artistic Director, South African Okwui Enzewor. Alongside a team of six co-curators representing, via birthplace or employment, four continents and a collective roster of impressive accomplishments, Enzewor organized D11 as a long-range project that began in 2001 with the first of five "Platforms," the fifth being the exhibition itself in Kassel, which ran from June through September of last year. But Platforms 1-4 were held starting in the spring of 2001 in Vienna; New Delhi; St. Lucia, West Indies; and Lagos, South Africa, respectively. Those Platforms were conferences and/or symposia with invited international speakers considering theoretical questions bearing upon the relations between cultures across the globe today (such themes as "Democracy Unrealized;" and "Experiments with Truth: Transitional Justice and the Processes of Truth and Reconciliation"). However, nowhere on the extensive D11 website, which contains complete curatorial resumes and videos of the platform-symposia, nor in the massive exhibition catalog, is the exact relationship between the conference platforms, and the works on view in Kassel, ever made clear. (Official publications about the individual platforms may do this, but they have been slow to appear.) What, exactly, did those geographically dispersed conferences have to do with the actual selection of art works in Kassel? Anything? And just how did the first four Platforms affect the exhibition's overall scheme?

In an interview with Carol Becker of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago,

published in Art Journal (Summer 2002) Enzewor explains:

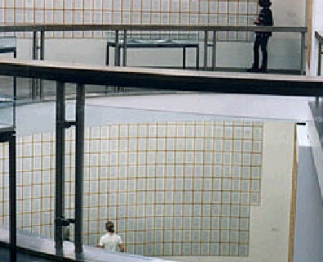

Hann Darboven,

Life/Living, 1997-98.

Photo: Hope Childers.  What does reflect the discursive processes leading up to the exhibition is the unmistakable political and theoretical thrust of the works on view, overwhelmingly dedicated to matters associated with the (primarily negative, and worsening) effects of post-colonialism and globalization. Take for example Cildo Miereles's elegant Disappearing Element/Disappeared Element (Immanent Past), 2002. During the exhibition, strolling vendors sold popsicles for a Euro apiece, each on a stick bearing the work's title. The popsicles, made of water, are of course flavorless and colorless, and quickly melt (disappear) if not consumed, calling attention to political-ecological issues (disparities in world access to plentiful and safe water); world trade issues (water as a vehicle as well as a producer of power); and art-politics issues (the ice melts, thus defying notions of possession and display of artworks). More baldly political (and yet more visually beautiful) was Alan Sekula's Fish Story, an artwork-as-documentary that, before it arrived in Kassel, already had traveled an exhibition route through Europe and America since 1995 and also exists as a separate publication. Sekula uses primarily large-format photography and text to draw attention to the effects of global capitalism on several port cities, some of the most crucial yet overlooked vectors in the history and processes of globalization. He explores these border points as physical and virtual boundaries that are permeated by power - ful but hard-to-detect forces with far-reaching natural and cultural implications. Other political works pit information against fear to create a sense of unease or distress in the audience. For example, Tania Bruguera's untitled installation subjects viewers to blinding floodlights and the loud sounds of an unseen sentry marching and loading a shotgun. Viewers are rendered powerless and in direct relationship to the subjects of political power who were present at any of the roster of world tragedies listed in a slide projection on the wall (visible only when the floodlights went dim) in which place names and dates, like "Mai Lai 1968" and "Haiti 1985-86," alternate with a repeated scene of a man running in the dark. But most presentations are less dramatic and more often require viewers to complete sizable reading loads (extensive wall or website texts) in order to comprehend their complexity. This is the case with Fareed Armaly's From/To (2002), a metaphorical network based on a digital image of the surface of a stone schematized to represent the geography of the Palestinian territories. Armaly, in collaboration with Rasheed Masharawi and other artists, fills several large spaces in the Halle with documentary video, film, text and sound pieces to complicate the geographical reference with multilevel particularities of the Mid-East conflict. Those who traveled to Kassel expecting to see cutting-edge media or display found little of it; the majority of works were in tried-and-true formats: glossy, slide-box photography, single-channel video or digitized film in dark, isolating cubicles, whole-room installations stuffed with personal/material refuse, collections of archival data, and so forth. Amid this array, a number of presentations triggered questions like, "does this work belong in an art exhibition, or somewhere else?" or, "why am I looking at this here rather than sitting home and reading it as a book or interacting with a website?"

Lorna Simpson, 31 2002, 2002.

Photo: Hope Childers.  One wonders if Bode had an inkling of how revealing the name "Documenta" eventually would become. The term suggests documentation as in an archive, and implies that D11 might best be seen as a research and development lab (as Enzewor has stated), rather than an exhibition in the traditional sense. In his preface to the Exhibition Short Guide (Kassel: Hatje Cantz Verlag; distributed by DAP), Enzewor says, ". . . Documenta's five platforms, in a necessary but critical move, begin with a series of dematerializations, which not only intervene in the historical location of Documenta in Kassel, but also emblematize the mechanisms that make the space of contemporary art one of multiple ruptures." But if this is the case, why is so much of the work in Platform 5 (the exhibition itself) formatted and presented in rather traditional ways? Why so little truly interactive work in the sense of open and collective or copylefted authorship? Some might answer that, in order to address their global concerns, the curators felt they could not demand a high level of technological capability or theoretical expertise (on the part of either artist or audience), and to have done so would have been to present, once again, an elitist "art world" production.

Cerith Wyn Evans, The Accursed Share,

2002.

Photo: Hope Childers  If Documenta11_Platform5 is indeed an art exhibition as "research," and if it is meant to "rupture" contemporary art's complacent role in society, then it is an undertaking that remains necessarily incomplete: an ongoing project that must be "finished" by its audience, who, in reality, often does not (for whatever reason) have enough information or patience for the task, or, at least, not in the traditional museum context. The entire event may be emblematic of our age: our society's inability to keep up its own technical capabilities. The curators (perhaps with the best conceptualist intentions) have amassed, in a formally rigid manner, an enormous wealth of information (data input) with no guidelines on how we are to process it all. While this is not bad in itself, in practical terms such a strategy can be exhausting for the individual viewer. Indeed, though Documenta11_ Platform5 attracted millions this year, who, exactly, was its target audience? When we visited the exhibition over a period of six days in July, we heard mostly European languages spoken around us. Even with all its Platforms, how could D11 really impact communities in the far reaches of the globe? This is not a frivolous question. Yes, this Documenta must be praised for its vast international reach, and (living up to its tradition) for its contribution to the discourse on art's role in today's world. Yet, if the point of Platforms 1-4 was to provide a means by which communities normally marginalized in the art world could engage in this discourse, their overall contribution has been lost in the translation, so to speak, and it remains to be seen whether these initiatives will constitute an ongoing practice or if they have already fizzled out. By now, there has been time for discussion and opinion to circulate on the Web via mailing lists, weblogs, and online journals, but participation in these is restricted to those with Internet access. D11 also reminds us that institutions are inherently slow on the uptake in assimilating new technology, fresh attitudes, and the latest debates, and they are not geared towards networking culture. While there is certainly cause for complaint when the hands of the Director and his curatorial team are too keenly felt in an exhibition, Documenta11_Platform5 seems to argue that the reverse is also true: a passive, invisible, or merely formal curatorial style can be just as frustrating. Rather, curators must learn to adapt, connect, and expand their brief. Today, they need to add to their customary tasks the functions of archivists, architects web designers and editors, and orchestrate all these roles, in order to craft a new kind of exhibition that also addresses the formidable task of communication and helps the viewer/audience negotiate the accelerating flow of information in a fundamentally transformed post-colonial art arena. |