|

How We Made Our Own "Carnivore"by RSG |

|

Hacking

Today

there are generally two things said about hackers. They are either terrorists

or libertarians. Historically the word meant an amateur tinkerer, an autodictat

who might try a dozen solutions to a problem before eking out success.[2]

Aptitude and perseverance have always eclipsed rote knowledge in the hacking

community. Hackers are the type of technophiles you like to have around

in a pinch, for given enough time they generally can crack any problem

(or at least find a suitable kludge). Thus, as Bruce Sterling writes, the

term hacker "can signify the free-wheeling intellectual exploration of

the highest and deepest potential of computer systems."[3] Or as the glowing

Steven Levy reminisces of the original MIT hackers of the early sixties,

"they were such fascinating people. [...] Beneath their often unimposing

exteriors, they were adventurers, visionaries, risk-takers, artists...and

the ones who most clearly saw why the computer was a truly revolutionary

tool."[4] These types of hackers are freedom fighters, living by the dictum

that data wants to be free.[5] Information should not be owned, and even

if it is, non-invasive browsing of such information hurts no one. After

all, hackers merely exploit preexisting holes made by clumsily constructed

code.[6] And wouldn't the revelation of such holes actually improve data

security for everyone involved?

"Disobedience to authority is one of theYet after a combination of public technophobia and aggressive government legislation, the identity of the hacker changed in the US in the mid to late eighties from do-it-yourself hobbyist to digital outlaw.[7] Such legislation includes the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986 which made it a felony to break into federal computers. "On March 5, 1986," reported Knight Lightning of Phrack magazine, "the following seven phreaks were arrested in what has come to be known as the first computer crime 'sting' operation. Captain Hacker \ Doctor Bob \ Lasertech \ The Adventurer [\] The Highwayman \ The Punisher \ The Warden."[8] "[O]n Tuesday, July 21, 1987," Knight Lightning continued, "[a]mong 30-40 others, Bill From RNOC, Eric NYC, Solid State, Oryan QUEST, Mark Gerardo, The Rebel, and Delta-Master have been busted by the United States Secret Service."[9] Many of these hackers were targeted due to their "elite" reputations, a status granted only to top hackers. Hackers were deeply discouraged by their newfound identity as outlaws, as exemplified in the famous 1986 hacker manifesto written by someone calling himself[10] The Mentor: "We explore... and you call us criminals. We seek after knowledge... and you call us criminals."[11] Because of this semantic transformation, hackers today are commonly referred to as terrorists, nary-do-wells who break into computers for personal gain. So by the turn of the millennium, the term hacker had lost all of its original meaning. Now when people say hacker, they mean terrorist.

most natural and healthy acts."

-Empire, Hardt & Negri

Thus,

the current debate on hackers is helplessly throttled by the discourse

on contemporary liberalism: should we respect data as private property,

or should we cultivate individual freedom and leave computer users well

enough alone? Hacking is more sophisticated than that. It suggests a future

type of cultural production, one that RSG seeks to embody in Carnivore.

Collaboration

Bruce Sterling writes that the late Twentieth Century is a moment of transformation from a modern control paradigm based on centralization and hierarchy to a postmodern one based on flexibility and horizontalization:

"For years now, economists and management theorists have speculated that the tidal wave of the information revolution would destroy rigid, pyramidal bureaucracies, where everything is top-down and centrally controlled. Highly trained "employees" would take on greater autonomy, being self-starting and self-motivating, moving from place to place, task to task, with great speed and fluidity. "Ad-hocracy" would rule, with groups of people spontaneously knitting together across organizational lines, tackling the problem at hand, applying intense computer-aided expertise to it, and then vanishing whence they came."[12]From Manuel Castells to Hakim Bey to Tom Peters this rhetoric has become commonplace. Sterling continues by claiming that both hacker groups and the law enforcement officials that track hackers follow this new paradigm: "they all look and act like `tiger teams' or `users' groups.' They are all electronic ad-hocracies leaping up spontaneously to attempt to meet a need."[13] By "tiger teams" Sterling refers to the employee groups assembled by computer companies trying to test the security of their computer systems. Tiger teams, in essence, simulate potential hacker attacks, hoping to find and repair security holes. RSG is a type of tiger team.

The term also alludes to the management style known as Toyotism originating in Japanese automotive production facilities. Within Toyotism, small pods of workers mass together to solve a specific problem. The pods are not linear and fixed like the more traditional assembly line, but rather are flexible and reconfigurable depending on whatever problem might be posed to them.

Management

expert Tom Peters notes that the most successful contemporary corporations

use these types of tiger teams, eliminating traditional hierarchy within

the organizational structure. Documenting the management consulting agency

McKinsey & Company, Peters writes: "McKinsey is a huge company. Customers

respect it. [...] But there is no traditional hierarchy. There are no organizational

charts. No job descriptions. No policy manuals. No rules about managing

client engagements. [...] And yet all these things are well understood-make

no mistake, McKinsey is not out of control! [...] McKinsey works. It's

worked for over half a century."[14] As Sterling suggests, the hacker community

also follows this organizational style. Hackers are autonomous agents that

can mass together in small groups to attack specific problems. As the influential

hacker magazine Phrack was keen to point out, "ANYONE can write for Phrack

Inc. [...] we do not discriminate against anyone for any reason."[15] Flexible

and versatile, the hacker pod will often dissolve itself as quickly as

it formed and disappear into the network. Thus, what Sterling and others

are arguing is that whereby older resistive forces were engaged with "rigid,

pyramidal bureaucracies," hackers embody a different organizational management

style (one that might be called "protocological"). In this sense, while

resistance during the modern age forms around rigid hierarchies and bureaucratic

power structures, resistance during the postmodern age forms around the

protocological control forces existent in networks.

Management

expert Tom Peters notes that the most successful contemporary corporations

use these types of tiger teams, eliminating traditional hierarchy within

the organizational structure. Documenting the management consulting agency

McKinsey & Company, Peters writes: "McKinsey is a huge company. Customers

respect it. [...] But there is no traditional hierarchy. There are no organizational

charts. No job descriptions. No policy manuals. No rules about managing

client engagements. [...] And yet all these things are well understood-make

no mistake, McKinsey is not out of control! [...] McKinsey works. It's

worked for over half a century."[14] As Sterling suggests, the hacker community

also follows this organizational style. Hackers are autonomous agents that

can mass together in small groups to attack specific problems. As the influential

hacker magazine Phrack was keen to point out, "ANYONE can write for Phrack

Inc. [...] we do not discriminate against anyone for any reason."[15] Flexible

and versatile, the hacker pod will often dissolve itself as quickly as

it formed and disappear into the network. Thus, what Sterling and others

are arguing is that whereby older resistive forces were engaged with "rigid,

pyramidal bureaucracies," hackers embody a different organizational management

style (one that might be called "protocological"). In this sense, while

resistance during the modern age forms around rigid hierarchies and bureaucratic

power structures, resistance during the postmodern age forms around the

protocological control forces existent in networks.

Coding

In 1967 the artist Sol LeWitt outlined his definition of conceptual art:

"In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art."[16]LeWitt's perspective on conceptual art has important implications for code, for in his estimation conceptual art is nothing but a type of code for artmaking. LeWitt's art is an algorithmic process. The algorithm is prepared in advance, and then later executed by the artist (or another artist, for that matter). Code thus purports to be multidimensional. Code draws a line between what is material and what is active, in essence saying that writing (hardware) cannot do anything, but must be transformed into code (software) to be affective. Northrop Frye says a very similar thing about language when he writes that the process of literary critique essentially creates a meta text, outside of the original source material, that contains the critic's interpretations of that text.[17] In fact, Kittler defines software itself as precisely that "logical abstraction" that exists in the negative space between people and the hardware they use.[18]

Code is a language, but a very special kind of language.How can code be so different than mere writing? The answer to this lies in the unique nature of computer code. It lies not in the fact that code is sub-linguistic, but rather that it is hyper-linguistic. Code is a language, but a very special kind of language. Code is the only language that is executable. As Kittler has pointed out, "[t]here exists no word in any ordinary language which does what it says. No description of a machine sets the machine into motion."[19] So code is the first language that actually does what it says--it is a machine for converting meaning into action.[20] Code has a semantic meaning, but it also has an enactment of meaning. Thus, while natural languages such as English or Latin only have a legible state, code has both a legible state and an executable state. In this way, code is the summation of language plus an executable meta-layer that encapsulates that language.

Code is the only language that is executable

Dreaming

Fredric Jameson said somewhere that one of the most difficult things to do under contemporary capitalism is to envision utopia. This is precisely why dreaming is important. Deciding (and often struggling) for what is possible is the first step for a utopian vision based in our desires, based in what we want.

Pierre Lévy is one writer who has been able to articulate eloquently the possibility of utopia in the cyberspace of digital computers.[21] "Cyberspace," he writes, "brings with it methods of perception, feeling, remembering, working, of playing and being together. [...] The development of cyberspace [...] is one of the principle aesthetic and political challenges of the coming century."[22] Lévy's visionary tone is exactly what Jameson warns is lacking in much contemporary discourse. The relationship between utopia and possibility is a close one. It is necessary to know what one wants, to know what is possible to want, before a true utopia may be envisioned.

Once of the most important signs of this utopian instinct is the hacking community's anti-commercial bent. Software products have long been developed and released into the public domain, with seemingly no profit motive on the side of the authors, simply for the higher glory of the code itself. "Spacewar was not sold," Steven Levy writes, referring to the early video game developed by several early computer enthusiasts at MIT. "Like any other program, it was placed in the drawer for anyone to access, look at, and rewrite as they saw fit."[23] The limits of personal behavior become the limits of possibility to the hacker. Thus, it is obvious to the hacker that one's personal investment in a specific piece of code can do nothing but hinder that code's overall development. "Sharing of software [...] is as old as computers," writes free software guru Richard Stallman, "just as sharing of recipes is as old as cooking."[24] Code does not reach its apotheosis for people, but exists within its own dimension of perfection. The hacker feels obligated to remove all impediments, all inefficiencies that might stunt this quasi-aesthetic growth. "In its basic assembly structure," writes Andrew Ross, "information technology involves processing, copying, replication, and simulation, and therefore does not recognize the concept of private information property."[25] Commercial ownership of software is the primary impediment hated by all hackers because it means that code is limited--limited by intellectual property laws, limited by the profit motive, limited by corporate "lamers."

However,

greater than this anti-commercialism is a pro-protocolism. Protocol, by

definition, is "open source," the term given to a technology that makes

public the source code used in its creation. That is to say, protocol is

nothing but an elaborate instruction list of how a given technology should

work, from the inside out, from the top to the bottom, as exemplified in

the RFCs, or "Request For Comments" documents. While many closed source

technologies may appear to be protocological due to their often monopolistic

position in the market place, a true protocol cannot be closed or proprietary.

It must be paraded into full view before all, and agreed to by all. It

benefits over time through its own technological development in the public

sphere. It must exist as pure, transparent code (or a pure description

of how to fashion code). If technology is proprietary, it ceases to be protocological.

However,

greater than this anti-commercialism is a pro-protocolism. Protocol, by

definition, is "open source," the term given to a technology that makes

public the source code used in its creation. That is to say, protocol is

nothing but an elaborate instruction list of how a given technology should

work, from the inside out, from the top to the bottom, as exemplified in

the RFCs, or "Request For Comments" documents. While many closed source

technologies may appear to be protocological due to their often monopolistic

position in the market place, a true protocol cannot be closed or proprietary.

It must be paraded into full view before all, and agreed to by all. It

benefits over time through its own technological development in the public

sphere. It must exist as pure, transparent code (or a pure description

of how to fashion code). If technology is proprietary, it ceases to be protocological.

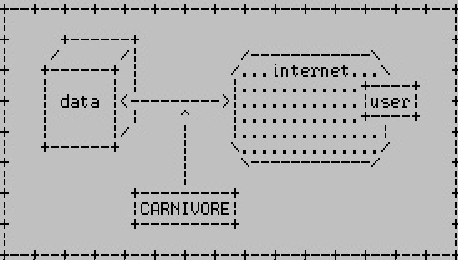

This

brings us back to Carnivore, and the desire to release a public domain

version of a notorious surveillance tool thus far only available to government

operatives. The RSG Carnivore levels the playing field, recasting art and

culture as a scene of multilateral conflict rather than unilateral domination.

It opens the system up for collaboration within and between client artists.

It uses code to engulf and modify the original FBI apparatus.

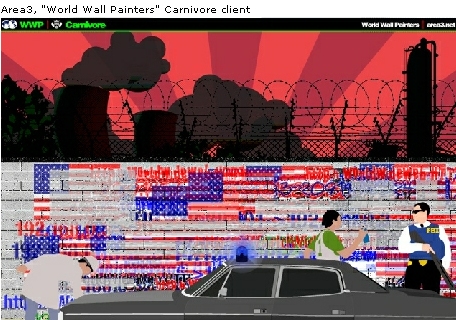

Carnivore Personal Edition

On

October 1, 2001, three weeks after the 9/11 attacks in the US, the Radical

Software Group (RSG) announced the release of Carnivore, a public domain

riff on the notorious FBI software called DCS1000 (which is commonly referred

to by its nickname "Carnivore"). While the FBI software had already been

in existence for some time, and likewise RSG had been developing its version

of the software since January 2001, 9/11 brought on a crush of new surveillance

activity. Rumors surfaced that the FBI was installing Carnivore willy-nilly

on broad civilian networks like Hotmail and AOL with the expressed purpose

of intercepting terror-related communication. As Wired News reported on

September 12, 2001, "An administrator at one major network service provider

said that FBI agents showed up at his workplace on [September 11] `with

a couple of Carnivores, requesting permission to place them in our core.'"

Officials at Hotmail were reported to have been "cooperating" with FBI

monitoring requests. Inspired by this activity, the RSG's Carnivore sought

to pick up where the FBI left off, to bring this technology into the hands

of the general public for greater surveillance saturation within culture.

The first RSG Carnivore ran on Linux. An open source schematic was posted

on the net for others to build their own boxes. New functionality was added

to improve on the FBI-developed technology (which in reality was a dumbed-down

version of tools systems administrators had been using for years). An initial

core (Alex Galloway, Mark Napier, Mark Daggett, Joshua Davis, and others)

began to build interpretive interfaces. A testing venue was selected: the

private offices of Rhizome.org at 115 Mercer Street in New York City, only

30 blocks from Ground Zero. This space was out-of-bounds to the FBI, but

open to RSG.

On

October 1, 2001, three weeks after the 9/11 attacks in the US, the Radical

Software Group (RSG) announced the release of Carnivore, a public domain

riff on the notorious FBI software called DCS1000 (which is commonly referred

to by its nickname "Carnivore"). While the FBI software had already been

in existence for some time, and likewise RSG had been developing its version

of the software since January 2001, 9/11 brought on a crush of new surveillance

activity. Rumors surfaced that the FBI was installing Carnivore willy-nilly

on broad civilian networks like Hotmail and AOL with the expressed purpose

of intercepting terror-related communication. As Wired News reported on

September 12, 2001, "An administrator at one major network service provider

said that FBI agents showed up at his workplace on [September 11] `with

a couple of Carnivores, requesting permission to place them in our core.'"

Officials at Hotmail were reported to have been "cooperating" with FBI

monitoring requests. Inspired by this activity, the RSG's Carnivore sought

to pick up where the FBI left off, to bring this technology into the hands

of the general public for greater surveillance saturation within culture.

The first RSG Carnivore ran on Linux. An open source schematic was posted

on the net for others to build their own boxes. New functionality was added

to improve on the FBI-developed technology (which in reality was a dumbed-down

version of tools systems administrators had been using for years). An initial

core (Alex Galloway, Mark Napier, Mark Daggett, Joshua Davis, and others)

began to build interpretive interfaces. A testing venue was selected: the

private offices of Rhizome.org at 115 Mercer Street in New York City, only

30 blocks from Ground Zero. This space was out-of-bounds to the FBI, but

open to RSG.

The

initial testing proved successful and led to more field-testing at the

Princeton Art Museum (where Carnivore was quarantined like a virus into

its own subnet) and the New Museum in New York. During the weekend of February

1st 2002, Carnivore was used at Eyebeam to supervise the hacktivists protesting

the gathering of the World Economic Forum.

Sensing

the market limitations of a Linux-only software product, RSG released Carnivore

Personal Edition (PE) for Windows on April 6, 2002. CarnivorePE brought

a new distributed architecture to the Carnivore initiative by giving any

PC user the ability to analyze and diagnose the traffic from his or her

own network. Any artist or scientist could now use CarnivorePE as a surveillance

engine to power his or her own interpretive "Client." Soon Carnivore Clients

were converting network traffic to sound, animation, and even 3D worlds,

distributing the technology across the network.

The

prospect of reverse- engineering the original FBI software was uninteresting

to RSG. Crippled by legal and ethical limitations, the FBI software needed

improvement not emulation. Thus CarnivorePE features exciting new functionality

including artist-made diagnosic clients, remote access, full subject targetting,

full data targetting, volume buffering, transport protocol filtering, and

an open source software license. Reverse-engineering is not necessarily

a simple mimetic process, but a mental upgrade as well. RSG has no desire

to copy the FBI soft-ware and its many shortcomings.

Instead, RSG longs to inject progressive politics back into a fundamentally destabilizing and transformative technology, packet sniffing. Our goal is to invent a new use for data surveillance that breaks out of the hero/terrorist dilemma and instead dreams about a future use for networked data.

http://rhizome.org/carnivore

http://rhizome.org/RSG

NOTES:

[1]

The system at the University of Hawaii was called ALOHAnet and was created

by Norman Abramson. Later the technology was further developed by Robert

Metcalfe at Xerox PARC and dubbed "Ethernet."

[2] Robert Graham traces the etymology of the term to the sport of golf: "The word `hacker' started out in the 14th century to mean somebody who was inexperienced or unskilled at a particular activity (such as a golf hacker). In the 1970s, the word `hacker' was used by computer enthusiasts to refer to themselves. This reflected the way enthusiasts approach computers: they eschew formal education and play around with the computer until they can get it to work. (In much the same way, a golf hacker keeps hacking at the golf ball until they get it in the hole.) http://www.robertgraham.com/pubs/hacking-dict.html.

[3] Bruce Sterling The Hacker Crackdown (New York: Bantam, 1992), p. 51. See also Hugo Cornwall's Hacker's Handbook (London: Century, 1988), which characterizes the hacker as a benign explorer. Cornwall's position highlights the differing attitudes between the US and Europe, where hacking is much less criminalized and in many cases prima facie legal.

[4] Steven Levy, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution (New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1984), p. ix.

[5] This slogan is attributed to Stewart Brand, who wrote that "[o]n the one hand information wants to be expensive, because it's so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life. On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of getting it out is getting lower and lower all the time. So you have these two fighting against each other." See Whole Earth Review, May 1985, p. 49.

[6] Many hackers believe that commercial software products are less carefully crafted and therefore more prone to exploits. Perhaps the most infamous example of such an exploit, one which critiques software's growing commercialization, is the "BackOrifice" software application created by the hacker group Cult of the Dead Cow. A satire of Microsoft's "Back Office" software suite, BackOrifice acts as a Trojan Horse to allow remote access to personal computers running Microsoft's Windows operating system.

[7] For an excellent historical analysis of this transformation see Sterling's The Hacker Crackdown. Andrew Ross explains this transformation by citing, as do Sterling and others, the increase of computer viruses in the late eighties, especially "the viral attack engineered in November 1988 by Cornell University hacker Robert Morris on the national network system Internet. [.] While it caused little in the way of data damage [.], the ramifications of the Internet virus have helped to generate a moral panic that has all but transformed everyday 'computer culture. '" See Andrew Ross, Strange Weather: Culture, Science, and Technology in the Age of Limits (New York: Verso, 1991), p. 75.

[8] Knight Lightning, "Shadows Of A Future Past," Phrack, vol. 2, no. 21, file 3.

[9] Knight Lightning, "The Judas Contract," Phrack, vol. 2, no. 22, file 3.

[10] While many hackers use gender neutral pseudonyms, the online magazine Phrack, with which The Mentor was associated, was characterized by its distinctly male staff and readership. For a sociological explanation of the gender imbalance within the hacking community, see Paul Taylor, Hackers: Crime in the digital sublime (New York: Routledge, 1999), pp. 32-42.

[11] The Mentor, "The Conscience of a Hacker," Phrack, vol. 1, no. 7, file 3. http://www.iit.edu/~beberg/manifesto.html

[12] Sterling, The Hacker Crackdown, p. 184. [13] Ibid.

[14] Tom Peters, Liberation Management: Necessary Disorganization for the Nanosecond Nineties (New York: Knopf, 1992), pp. 143-144. An older, more decentralized (rather than distributed) style of organizational management is epitomized by Peter Drucker's classic analysis of General Motors in the thirties and forties. He writes that "General Motors considers decentralization a basic and universally valid concept of order." See Peter Drucker, The Concept of the Corporation (New Brunswick: Transaction, 1993), p. 47.

[15] "Introduction," Phrack, v. 1, no. 9, phile [sic] 1.

[16] Sol LeWitt, "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art," in Alberro, et al., eds., Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999), p. 12. Thanks to Mark Tribe for bring this passage to my attention.

[17] See Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1957). See also Fredric Jameson's engagement with this same subject in "From Metaphor to Allegory" in Cynthia Davidson, Ed., Anything (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001).

[18] Friedrich Kittler, "On the Implementation of Knowledge-Toward a Theory of Hardware," nettime (http://www.nettime.org/nettime.w3archive/19 9902/msg00038.html).

[19] Kittler, "On the Implementation of Knowledge."

[20] For an interesting commentary on the aesthetic dimensions of this fact see Geoff Cox, Alex McLean and Adrian Ward's "The Aesthetics of Generative Code" (http://side-stream.org/papers/aesthetics/). [21] Another is the delightfully schizophrenic Ted Nelson, inventor of hypertext. See Computer Lib/Dream Machines (Redmond, WA: Tempus/Microsoft, 1987).

[22] Pierre Lévy, L'intelligence collective: Pour une anthropologie du cyberspace (Paris: Editions la Découverte, 1994), p. 120, translation mine.

[23] Levy, Hackers, p. 53. In his 1972 Rolling Stone article on the game, Steward Brand went so far as to publish Alan Kay's source code for Spacewar right along side his own article, a practice rarely seen in popular publications. See Brand, "SPACEWAR," p. 58.

[24] Richard Stallman, "The GNU Project," available online at http://www.gnu.org/gnu/thegnuproject.html and in Chris Dibona (Editor), et al, Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution (Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly, 1999).

[25]

Ross, Strange Weather, p. 80.